Hard Mother

I’ve spent a lifetime becoming my mother. Since I can remember, I’ve been told I look just like her. After her death, her sister still sometimes calls me by her name. This year, I’ll arrive in time where her narrative began to collapse into quiet. At 48, she lost the ability to speak and learned that a tumor was ravaging her body from Broca’s area of the brain, where thought is translated into language.

My mother could hear me, but she couldn’t answer back. She was a woman full of stories—the most urgent at that time was something about birds—but she grew frustrated by having no way to tell them. The tumor took her words before it took her life. For her, the final months were thick with silence. No speech, no writing. I found a way to understand her, and I became her caretaker, her echo, and her memory’s steward.

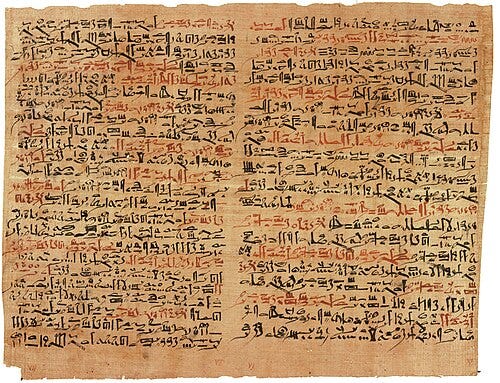

Lately I’ve been reading translations of the Edwin Smith Papyrus, which contains the earliest record of cancer. At nearly fifteen feet long, it lists trauma after trauma in meticulous order, and it describes eight cases of removing breast tumors. Beginning at the head and moving down the neck, arms, and torso, it documents injuries with startling clarity:

“If thou examines a man having bulging tumors on his breast, and thou findest they have spread over his breast... if thou puttest thy hand upon his breast, and thou findest they are cool, there being no fever at all therein... Say thou concerning him: one having bulging tumors. An ailment not to be treated.” 1

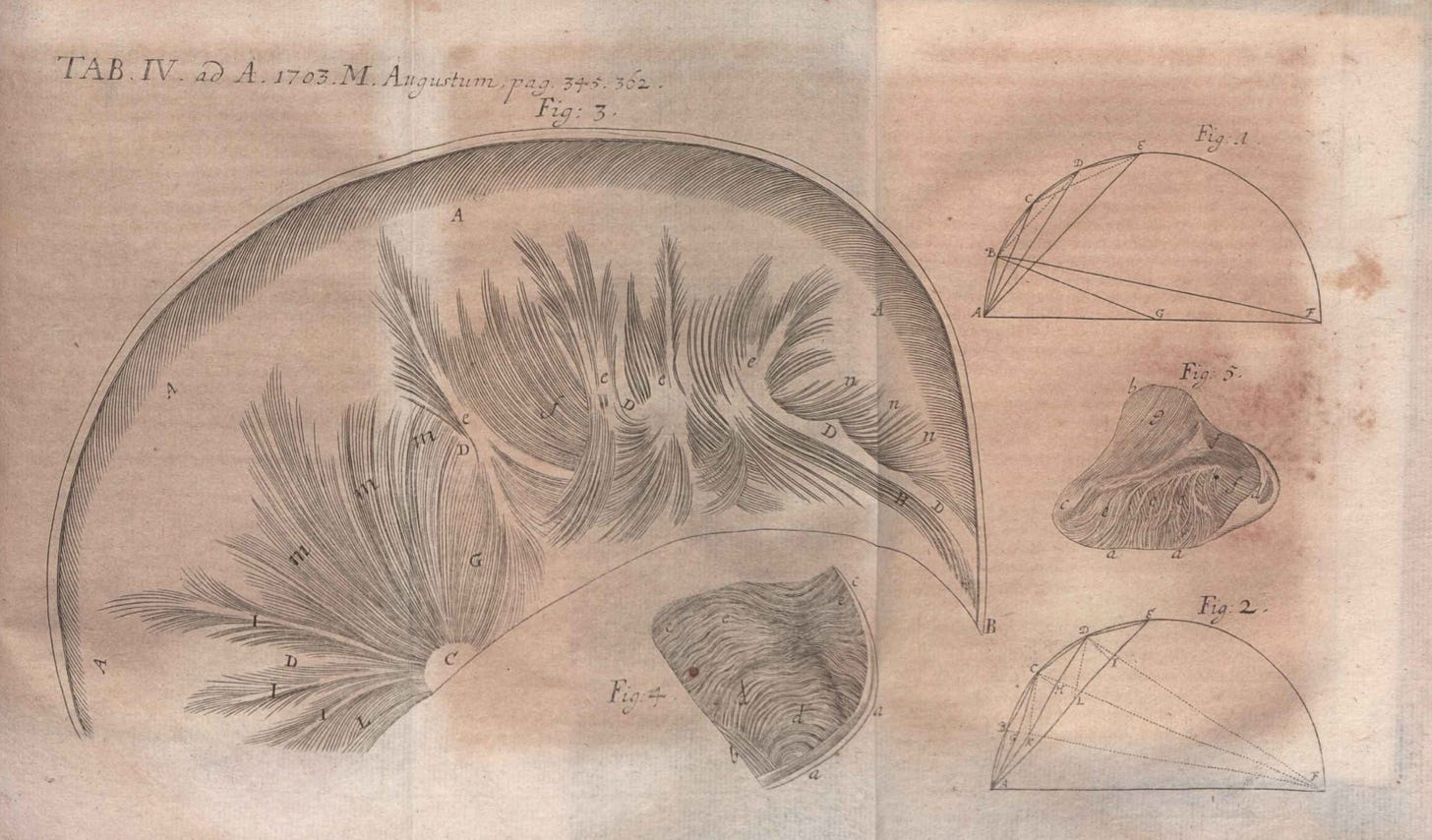

The diagnostic clarity is brutal. They knew what they could not cure, and they wrote about such inevitability. The Greeks, centuries later, named the disease karkinos or crab, for the way a tumor clings to the flesh and spreads outward like a crustacean’s limbs. Hippocrates described tumors as hard as a rocks. Galen later described the way veins around a breast tumor resembled a crab's legs. The Latin translation, cancer, has endured ever since. The name fits in more ways than one. Cancer is relentless, it holds on, it does not move directly. It circles and creeps. It returns. It hides beneath the shell of things.

I circle dates like a crab circles its prey, never head-on. My mother died on December 1st. Twenty-five years ago, or one life before—I’m not sure how to measure these distances: one year, one month, one week, one day, and one hour after my mother died, my son was born. Tiny and crying, he arrived like an anchor into the world. That number—so precise it sounds invented—marks a hinge in time, her silence and his sound stitched a flat-felled seam between absence and arrival. Language had left her and I had tasked myself to be its keeper.

Last year, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of her passing, I became a patient, a body with a mass that became a geography that was mapped, measured, and surveilled, terrain disrupted by core sampling and medical excavations. Cancer is the kind of word you should say with a practiced calm but instead I stayed silent while spiraling in a kind of crab’s path: obliquely, sidewinding, moving toward and away from myself in the same gait.

Spider Mother

Time, when it chooses to take shape, prefers to be in the round. We imagine a womb swelling into living form, a lesson in potential, an argument for patience. Or maybe the cycles of the moon, a body that grows by reflection rather than through accumulation. The tumor in my chest felt like a moon—hidden and tidal. We all know the moon rules Cancer, a water sign. This mass orbited something I couldn’t see, pulling at the waters in me, controlling cycles I no longer understood. I carried it as if my body were its own sky wondering how it became what it is. Dazed by the news and the appointments, the directions and injections, I wondered how Cancer, the most difficult constellation to see, arrived in the sky.

The constellation wasn’t always a crab. In ancient Egypt, it was a scarab beetle. In Mesopotamia, it was a turtle pushing the sun across the sky, bearing the weight of time and heat on its back. The slow, deliberate motion of a turtle across land or sea feels more accurate than the scuttle of a crab. More steady, ancient, and burdened. I have a turtle tattooed on my ankle, a reminder that slowness is not the opposite of survival.

Even the language of the body echoes these imaginings. The Edwin Smith Papyrus described the brain—the first time we have record of it—as surrounded by membranes called the meninges. They were named dura mater, arachnoid mater, pia mater: the hard mother, the spider mother, the tender mother. The spider mother spins her web around the brain like a mythic tether, and it's not lost on me that spiders and crabs belong to the same vast family of arthropods. Cancer is crab and spider and turtle, too, external and internal, hard-shelled and web-laced.

One of the most potent and personal explorations of motherhood and memory in contemporary art is Louise Bourgeois’s engagement with the image of the spider mother. Her iconic sculpture series Maman represents her mother, who was a weaver and worked in the family’s tapestry restoration business in France, patiently repairing what time had torn apart.

Bourgeois spent long periods of time caring for her mother, who she described as her best friend and who suffered from illness. Her mother died when Bourgeois was in her early twenties, a devastation that never left her. Reframing the spider from a symbol of fear into one of maternal care, protection, and silent industry became a central theme in her work and one of her favorite subjects.2

The Maman sculptures (it is an editioned work, so there are several) are physically overwhelming at over 30 feet tall, but somehow also emotionally tender. Viewers of the monumental work are permitted to walk underneath the spider’s body, which stands on eight legs that needle to sharp points where they touch the ground. This experience evokes the sense of awe that a small child might feel as they gaze upward toward their revered and much-needed mother. When gazing upward at Bourgeois’s spider, I see a sac that holds 32 white marble eggs. This and the work’s title makes clear that the spider is a mother, and suggests that I am being protected by a caretaker, though being trapped by something that might kill me remains a feasible and looming possibility.

Tender Mother

My mother was a Cancer sun, the sign of caretakers, the home, the tide, and intuition. I am a Cancer ascendant. Cancer season, the start of summer, a time of emotion and salt begins just after the solstice as this hard-shelled collection of stars pushes the sun to its peak. It is also Pride month. I think often about this convergence of water, sun, and rainbows, of caretaking and queerness, of bodies that do not conform to simple definitions.

Astrology tells us that Cancer rules the breasts, the chest, the place of love and sustenance and vulnerability. Medicine tells us the same, but more cruelly. Described as sites where madness begins: bitter taste, unclear vision, parched nipples, the sting in shoulder blades, the refusal of food, and finally the loss of self. The breasts, it turns out, were made myth even then. In this text the womb itself is “wandering,” “…an animal within an animal. It moves of its own accord, up and down the body.”3 These ancient diagnoses are as problematic as they are evocative, contributing to persistent medical beliefs that women’s bodies are inherently unstable, dangerous, and mysterious. Yes, maybe they are. When I used the internet to try and discover the origin of my disease it told me that being a woman and aging are my biggest risks, something I knew already.

I’ve always known that the body is never singular. It is relational, made meaningful through touch, absence, gesture, memory. To mother, in my case, was to rebuild a web. I am alive. To become a woman, to host life, to discover queerness, to approach illness or death is to wander and to wonder. My treatment was successful. I am cancer-free, which I write like an incantation. But I continue to live underneath a spider mother, under the same moon, in the same sign.

I cannot say if lineage is a curse or a calling. But I’ve mothered in the shadow of my mother’s death and I create in the echo of her silence. Recently I have been reviewing artwork I made more than a decade ago. I was able to read my own words reflected back to me in a book with a chapter section called Milk and Motherhood. The author describes a conversation we had in my studio: “She made a large container that hung down from the ceiling, dripping milk, ‘kind of like a tumor thing growing out of the ceiling.’”4

Further into the book, another section is titled The Cliché Breast. In this book about teaching creativity, two men discuss the "cliché breast" in undergraduate figure drawing as if drawing breasts were about copying an idea or observing an object. They critiqued figure drawings by undergrads with a careless remove, presuming their own originality while decrying the “predictability” of a breast rendered too familiarly. I rolled my eyes and felt a familiar indignance.

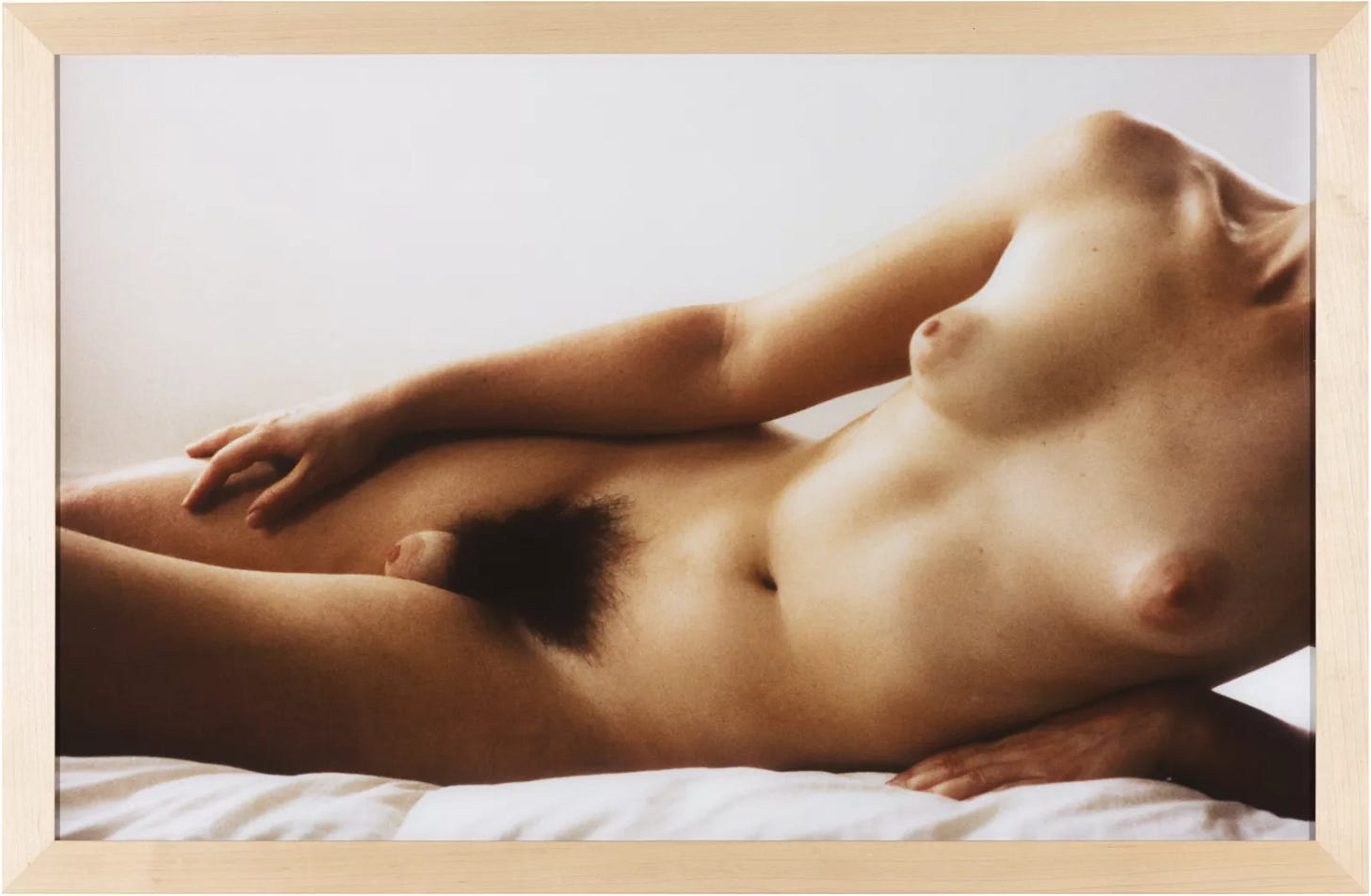

Reading the exchange reminded me of a photograph by Jeanne Dunning called The Third Breast in which the artist photographs a woman's body with an additional breast-like form—round, fleshy, clearly artificial but disturbingly plausible—added between her legs nestled into her pubic hair. The image is erotic and funny at once—disrupting normative visual codes of female sexuality. It suggests a kind of feminine excess, both in literal form and in symbolic weight: the female body as insistent and "too much.”

Dunning is known for her photographic works that destabilize norms. Her subjects often exist between authentic and artificial, erotic and grotesque. She uses photographic framing and lighting, flesh-like materials, and constructed body parts to disorient viewers, prompting them to confront what they perceive, unsettling all kinds of clichés of the body.

I recently saw Dunning’s Torso displayed at a museum, a photograph that presents a cropped image of a pale, fleshy human trunk. The image shows no head, hands, or feet—just the anonymous torso, abstracted through positioning and dramatic lighting. The image challenges the male gaze and traditional representations of the nude, playing with the history of the fragmented body in art while also suggesting a phallus.

Seeing this particular work in person reminded me of a series of small porcelain studies my mom made around the same time. They are smooth, ambiguous, and fragmentary. Trying to find them, I tore through boxes of packed books (I used to display the figures in my library, which is mostly packed while I prepare to move) and located the one I was looking for. I wanted to see if the similarly rendered form also evoked a penis if I laid it on its side. I suppose it does, slightly, but I was more struck by a detail I had never noticed before: the small white torso—spine curved into a concave and protective gesture—was missing one breast.

Lineage is not just blood, it’s how stories get told or go untold. This is the strange gravity of survival: you begin to understand things only when you can no longer ask about them. I can’t talk to my mother about how time dilates and contracts, about how motherhood and aging and illness remake your body and your memory. I can’t ask what it was like to feel her own language fail her. The curvature of time pulls me sideways through memory, biology, and fate. I think maybe all language is prosthetic, an extension of loss.

This summer, as the sun moves through Cancer, I will open a new gallery in Chicago called Post-. It is tiny, but it holds multitudes. The inaugural show is called Firmament, and it includes one of my mother’s porcelain studies and a new miniature work I’ve been making, among other artists’ works. The word firmament originally meant the arched vault of the heavens—believed to hold back the waters of the cosmos. To me, it means structure and expanse, holding and releasing, a body that keeps the sky from falling.

Language and the body have never been separate in my mind. I learned to listen to my mother’s body like a sentence—one that closed not with a period, but with parentheses. Her story never ended. It curved inward and held me. Broca’s area is the syntax-maker, the container of grammar. When it dies, language doesn’t just disappear—it wanders and flows. I had to speak for her then. Now as the moon waxes in Cancer, as my scar itches in the sweaty summer heat, I write for her and remember that the moon’s fullness is not a mass—it’s a phase, teaching time by disappearing, appearing, and then disappearing again.

Post-script

Some say a crab never lets go, but I’ve learned that’s not true. Once the threat disappears, the crab will release her grip on whatever it is she’s been holding on to.

James P. Allen, The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005).

Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress, and the Tangerine, directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach (New York: Zeitgeist Films, 2008), documentary film.

Hippocrates, Diseases of Women 2, in Hippocrates, Volume X: Diseases of Women 1–2, Diseases of Women 3, Nature of Women, Barrenness, ed. and trans. Paul Potter, Loeb Classical Library 472 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Keith Sawyer, Learning to See: Inside the World’s Leading Art and Design Schools (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2025), 78.